Photography and Video by

Muhammad Fadli

Writings by

Fatris MF

Prologue

INDONESIA CANNOT BE UNDERSTOOD SOLELY THROUGH FORMULAS, ECONOMIC GROWTH, BUSTLING MARKETS, AND CITIES THAT BLOOM AND SPRAWL ACROSS THE LAND- SCAPE. INDONESIA IS ALSO FULL OF DESOLATE AND OBSCURE PLACES, ISOLATED ISLANDS—PLACES THAT SOMETIMES PAINT THE IMAGE OF AN UNFORTUNATE COUNTRY.

The gate of the 'Welvaren' nutmeg plantation on Ai Island. The name 'Welvaren' comes from the Dutch word meaning "prosperity".

Surrounded by deep and wild seas, the Banda Islands are one of those forgotten places. But contrary to its presentday condition, the tiny archipelago was in fact coveted and fought over by powerful Western countries. The reason was a rare commodity that flourished on these tiny islands—spices.

In the past, “spice” was a mighty word. It launched expeditions into vast oceans that were previously uncharted by Europeans. Our world was mapped and reorganized by spice hunters. Because of the race to the Spice Islands, the Vatican divided the Earth into two hemispheres. But today, when spices have become as mundane as the word “spice” itself, the remote islands once exploited for centuries by European powers have now faded into obscurity, as if blotted from the world map.

I visited Banda for the first time when the Western monsoon wind was blowing in full force. Every year storm season closes off the islands for months. In hindsight, I should not have boarded the ship that took me across the Banda Sea in early 2014, when the storm was raging. On the main island of Naira, I stayed with a woman who took me in as her own son. I wanted to go to Run and Ai, two islands that were not too far from Naira, but my adopted mother forbade it. She said that during storm season, the angels of death were roaming around the Bandas. I had simply come at the wrong time. And so, I could only travel between Naira and three small islands that were close by, witnessing how thousands of lives were still dependent on spice-producing trees. I saw how the Bandanese lived side-by-side with old forts covered in moss, cannons, and other vestiges from centuries past that seemed trapped in a strange dimension.

Less than a year later, Muhammad Fadli repeated the same mistake. He came to Banda when the storm season was at its fiercest. At times like these, only the most fearless fishermen are willing to sail through the Banda Sea, and curiously, Banda attracts many people of this type. Unlike me, Fadli made the crossing to Ai Island, and came face-to-face with the rage of the Banda Sea in its truest form. The seven meter-long boat that Fadli boarded was at the mercy of the great ocean swells. He recounted how the tongue of the wave spilled into the boat, and how all the passengers desperately called on God, some even praying aloud—to the point of shouting—while quoting holy verses as the blood drained from their faces. Meanwhile in faraway Jakarta, Fadli’s first daughter was only three months old. He swore never to return to Banda.

Inter-islands boat ride during the Western monsoon season on the Banda Islands.

However, that oath was eventually put aside. In the middle of 2015, Fadli and I decided to collaborate on a project we later named The Banda Journal. We returned to Banda, at times together. We went back every season: during the harvest, amid the heat of the dry season, and even when storms whipped the Banda Sea into a frenzy. Sometimes we left the islands by plane, and at other times aboard a slow oil-powered ship.

In Banda, I saw Fadli living a life as well-ordered as a dictionary. He scheduled his days to a strict routine: waking up early, taking photos, having breakfast, taking photos, enjoying lunch and a nap, before taking more photos. As though obsessed, he went into sacred places and plantations (sometimes getting lost) while carrying his medium format film camera. In the digital era, he was still using obsolete technology that required a lot of effort. He said it was because he wanted to connect better with his subjects. I couldn’t understand it. Apart from that, Fadli liked the suspense that came from not knowing how his photos turned out. Over the course of six journeys to and from Banda, he used up 150 rolls of film. In an age of instant gratification, he still enjoyed outdated technology with all the problems that came with it.

I was far more relaxed. Sometimes I taught children at the local schools, attended wedding parties (even when I did not know the bride and groom), and went swimming. Every night I would go for a stroll, listening to local legends and talking to people about “unimportant” things: neverending hopes, trauma, fires and bloody conflicts, even the price of instant noodles.

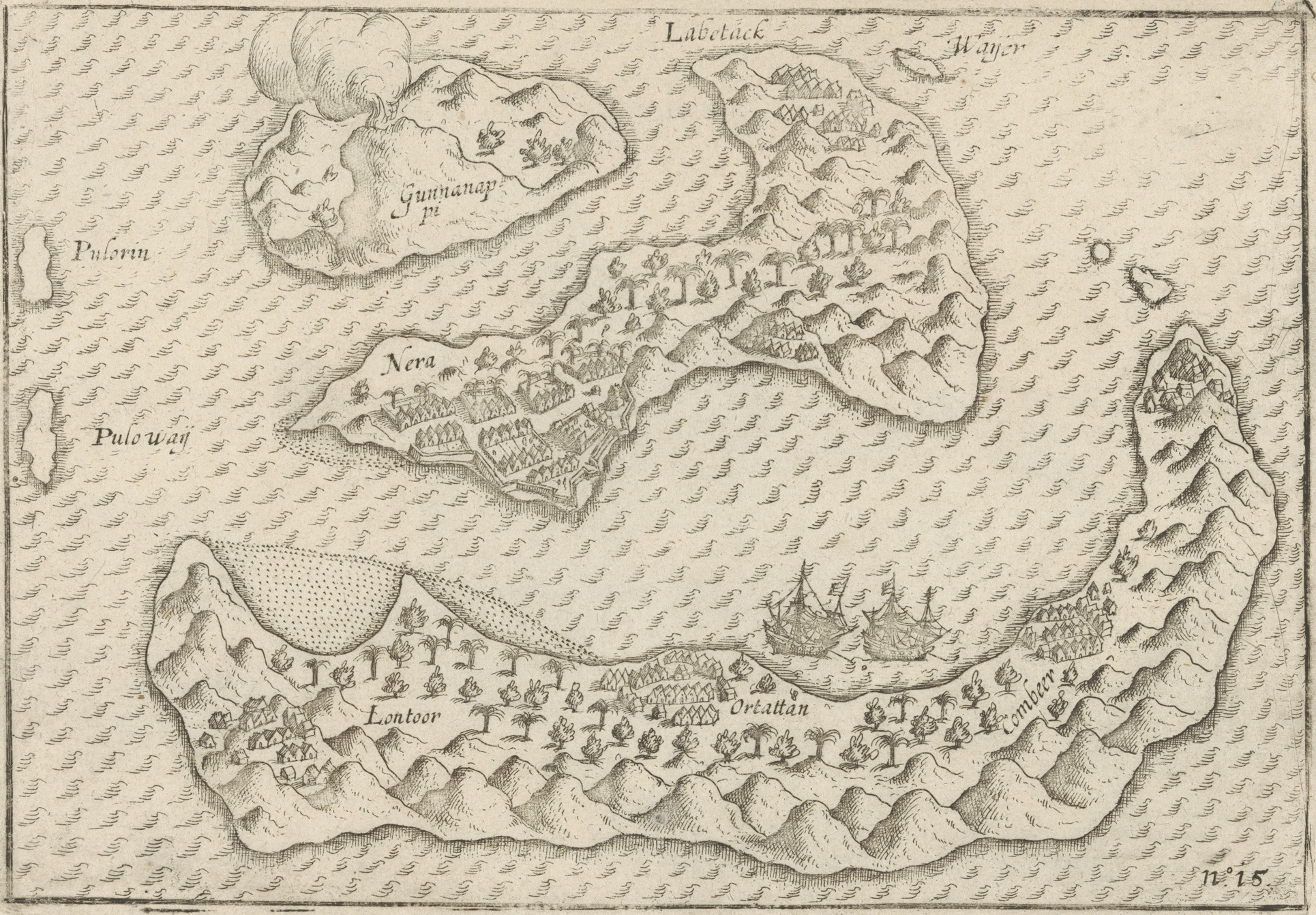

Map of the Banda Islands, made in 1599. This map is part of the illustrations in the travelogue of the second Dutch expedition to the East Indies led by Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck. Collection of Rijksmuseum.

After four visits to Banda, however, this book felt impossible to complete. Not only because I live on the western coast of Sumatra, a world away from Banda, but because I was not used to indepth research and complicated literature (at least according to my standards). There was also the fear of drowning in historical data and detailed colonial records; and how hard it was to grasp the fact that the Portuguese expeditions around the Cape of Good Hope and Columbus’ so called discovery of the Americas were all due to the search for an aromatic fruit in the Far East. How do I tell the story of a place whose destiny was determined by a plant?

This project was made not just to retrace history with various references and old texts, but also to raise awareness of the social conditions today in the spiceproducing islands. From our sojourns in this archipelago, we have tried to compose stories and photographs from fragments of the past that collide with the present. Banda is a valuable lesson about struggles, exploitation, pain, brutality, greed, and great deeds (sometimes bordering on the ridiculous) that test the limits of humankind.

Finally, the project tells of a tiny land that changed the world; we investigate what it once was and what it is today.

***

Next Chapter

All Rights Reserved © Jurnal Banda, The Banda Journal 2021